The purpose of this mission was to meet with our various contacts in India to discuss our future collaboration and to visit the sites of the red panda breeding and release centers, to learn more about these programs that are very important for the conservation of this species. For the Bhutan part, we also had to meet with the stakeholders involved in the protection of the red panda, and learn more about the programs implemented in the country. We will see throughout this report that our expectations were largely exceeded, and that great collaborations will be able to result from it.

We left on Monday, November 11, 2024, at Charles de Gaulle Airport in Paris, at 7:35 p.m. local time. At the gate, we were stopped and they checked our visas twice, telling us that we should have checked in at the airport, not online. Also, one of the backpacks was too big, but we boarded the plane anyway. The flight lasted 8 hours, with screens not working in our entire row... So we arrived at Indira Gandhi Airport on November 12, around 8 a.m. local time (4:30 hour time difference). Outside, the thermometer read 29°C. We changed terminals, to take a plane to Bagdogra (in West Bengal). This time, we went through check-in, and the bulky backpack ended up in the hold.

We arrived in Bagdogra around 3 p.m., and someone was waiting for us as we got off the plane. We then boarded a car for a 4.5-hour drive to Gangtok, stopping at the Sikkim border. Indian roads can be a bit chaotic, with people driving in all directions and dogs and cows wandering across the road.

We arrived in Bagdogra around 3 p.m., and someone was waiting for us as we got off the plane. We then boarded a car for a 4.5-hour drive to Gangtok, stopping at the Sikkim border. Indian roads can be a bit chaotic, with people driving in all directions and dogs and cows wandering across the road.

À l’hôtel « Mayfair », nous avons rencontré Mr Talpain (le consul général de France en Inde), Mr Mathou (l’ambassadeur de France en Inde) et sa femme, ainsi que Samuel Bouchard (chargé de mission au consulat général de France en Inde), qui nous accompagnera ensuite durant toute la durée de la mission.

Interviews in Sikkim

On November 13, we went to the Gangtok Zoo (Himalayan Zoological Park = HZP) for an official visit with the Consul General and the Ambassador. We also saw the red panda breeding center, a large enclosure divided into two parts by a fence, on a 1-hectare wooded area. This is the area that the zoo wants to completely isolate with a predator-proof perimeter wall., so that stray dogs cannot approach the enclosure. Indeed, they already have a return system at the top of the enclosure fence to prevent panthers from entering, but since canine distemper is contagious, the mere proximity of dogs around the enclosure can be enough to contaminate the pandas residing inside.

Then the consul and the ambassador left, and we had a meeting with Ms. Minla Zangmu Lachungpa, biologist and veterinarian at the HZP, and Mr. Sangay Gyatso Bhutia, director of the HZP, on the terms of our future collaboration. Minla explained to us the issues surrounding the breeding center, as well as their long-term project to build a larger breeding center further from the zoo, allowing for better reproduction of the pandas. The breeding pairs will therefore be kept away from visitors and the young will be presented in the zoo. But for the moment, the most important thing is to protect the current center, to allow the relaunch of the breeding program. Because at present, the HZP only has three red pandas, a mother accompanied by her two young (a male and a female).

During this interview, the director confirmed that as soon as we get the Delhi government's approval for the construction of the wall, he will send us the quotations so that we can start our fundraising campaign, and also assured us that we will then have reports on the construction of the wall. Minla said that she will be happy to help us adapt the Nepalese twinning booklet to Sikkim (list of species and scientific information).

So we sent her the booklet so she would have an idea of what it contains. They also agreed to distribute the booklet in schools and to intervene there to explain the issues.. As for establishing a relationship between schools, they advised us this idea: Set up an online platform to facilitate exchanges between schools. This idea is indeed interesting. Let's see how we can implement it, either directly from our website or by creating a dedicated space.

During the conversation, they also expressed their interest in participating, if we could organize it, in a webinar on good practices for caring for red pandas in captivity, with various topics, such as nutrition, for example, and exchanges between animal keepers. The director even offered to act as an interpreter for the Indian keepers.

At the end of the interview, they thanked us and assured us that they would be happy to welcome us back to the zoo. So we hit the road again, heading for Darjeeling (a 4.5-hour drive that was often chaotic and very winding), with a good feeling for the continuation of this collaboration. On the way, our driver took us for a break in one of the country's many "tea gardens," a vast field of tea plants.

Darjeeling: Zoo, breeding center and release site for red pandas

Thursday, November 14, 2024, we begin the day with a guided tour of the Darjeeling Zoo (Padmaja Naidu Himalayan Zoological Park = PNHZP), accompanied by a government forest service officer, Uttam Chandra Pradhan, and two zoo employees. There are almost exclusively Asian animals, herbivores and carnivores kept in enclosures adapted to their natural habitat (steep or not, forest environment or rather desert, etc.) and birds (mainly pheasants and doves, plus a few parrots). In the middle of the zoo stands a natural history museum, with stuffed animals, skeletons and skins.

Everything is very detailed, the animals are presented in their living environment and maps also show the distribution of the animals, at the level of West Bengal, then at the level of the country, the continent, and finally the world.

We were then welcomed into the office of the director of the Darjeeling Zoo, Dr. Basavaraj S. Holeyachi, who gave us a very detailed presentation (on PowerPoint) on the breeding of red pandas at the Darjeeling breeding center (Topkedara). He also presented the studies being conducted there, particularly in genetics, with the establishment of a biobank and cryopreservation, the loss of genetic diversity of red pandas (but this is applicable to many other species) being one of its main threats. This is due to the fragmentation of its habitat. It also seems that the subspecies Ailurus fulgens fulgens is more fragile with regard to inbreeding than the subspecies Ailurus fulgens styani. Then, he told us about the site of red panda release in West Bengal, the Singalila reserve. This reserve was chosen because, according to a study conducted there, there are only 32 red pandas left in this area. The aim of the reintroduction program is therefore to strengthen the wild population while increasing the genetic diversity of the population.

Each released individual is equipped with a GPS collar (developed by Rotterdam Zoo and adapted to the species), which allows it to be tracked by radio guidance for 70 weeks, and thus to conduct a parallel study on the ecology, habitat and lifestyle of the species. At the end of 70 weeks, when the battery is discharged, the collar falls off by itself. This allows, for example, to know the trees in which red pandas prefer to live, to then better adapt reforestation programs. Or, these studies also allow us to better understand the diet of the species, to better adapt the rations of red pandas in captivity.

Before starting the release process, a genetic study is conducted on several individuals and only those whose genome is most adapted, the most interesting for strengthening the wild population, will take part in the reintroduction program. They are then taken to special enclosures, to be "prepared" for release. They will then be "disaccustomed" to humans (the keepers begin to scare them if they get too close to them at feeding time). They will also move from the food ration they had at the breeding center to a more "natural" food, which they will find in their future habitat.

Finally, they are instilled with a fear of predators by combining their scent (e.g., urine or panther feces) with negative experiences, such as captures or veterinary care. They also sometimes bring dogs into the enclosure to see how the red pandas react to them. This can take three to six months. They are then taken to the release site in Singalila Park.

The program is currently planned for the next ten years, with releases every year. When we visited the breeding center, three female red pandas were being studied. Only two species currently have reintroduction programs in this region: the red panda and the Himalayan goral (a goat).

At the breeding center, biosecurity protocols are very strict, as are the quarantines of newly arrived animals, which are regularly tested for certain diseases/pathologies, depending on the season. A number of additional precautions may be applied during targeted periods. After our interview with the zoo director, we were able to see this during a tour of the breeding center.

We then set off again for the Singalila reserve, to spend the night there: 32 kilometers on a winding road that turned into a track for the last ten kilometers, most of the time just wide enough for a car, with a ravine on one side and the mountain on the other.

It takes about 3 hours to climb this mountain and reach the base camp, at an altitude of 3,636 meters. Throughout this route, we skirted Nepal: in fact, the road symbolizes the border between the two countries, which is why we had to show our passport and visa before entering the reserve. This base camp is the highest in Singalila Park. At 5:30 the next morning, we were able to watch the sunrise over the Himalayas, before descending back to the release site.

Coming down from the mountain on Friday, November 15, around 9:30 a.m., our driver stopped on the track to show us a wild red panda! As it turned out, our driver was a park guide, and was therefore used to looking for red pandas. He knew the spots where they could be seen, depending on the time of day. There, our little panda was comfortably settled on a Sorbus cuspidata ("tenga" in Nepali), a tree species much appreciated by the small mammal, who apparently loves its berries.

We then arrived at the release site, which covers an area of 1.7 hectares. This site is divided into two parts, each surrounded by a metal fence. In the first part, the red pandas are first placed in an acclimatization aviary, where they will stay for two days before the door is opened. In both parts, camera traps are installed in strategic locations (feeding areas, fences, doors, etc.). After two months spent in the first part, the door to the second part of the site is opened, the keepers continue to bring food but less and less, so that the pandas get used to searching the habitat themselves.

When they feel the individuals are ready, they open the door to the outside, so that the pandas can leave the "pre-release" areas.

After visiting the site, we took the car back to Siliguri (3 hours drive) to take the plane to Bhutan the next day.

Departure for Bhutan: Visit to the Royal Botanical Park

Bhutan is one of the five countries where the red panda is found in the wild. We had the opportunity to meet some of the people involved in its conservation in the country, so we jumped at the chance to learn more about the species, and, why not, extend our efforts there as well! We arrived in the "land of happiness" on the morning of Saturday, November 16, 2024. From the airport, a radical change of scenery, of landscape... Traditional buildings, a culture based on respect, a clean place, perched in the middle of the mountains. Here, you also find a few cows on the road, and a few stray dogs, but much fewer than in India.

From Paro Airport, we were picked up and taken to the capital of Bhutan, Thimphu, where we met our contact, Dr. Lungten Dorji, in charge of species conservation at the Department of Forest and Park Services (DoFPS), who would accompany us throughout our stay in Bhutan. He also took us to visit the Royal Botanical Garden, one of the country's protected areas, where we could also encounter a number of species of wild flora and fauna. In terms of wildlife, we only saw a cow, a dog, a cat, a few fish, birds, and a tame otter, which the park managers rescued after it had just gotten out of a fight with a dog. This one accompanied us for part of the journey. Not far from the park entrance, an information center presents educational panels on local flora and fauna, depending on the altitude, trophic networks, studies carried out on the park... a real mine of information for those interested!

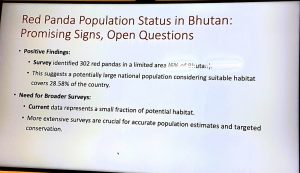

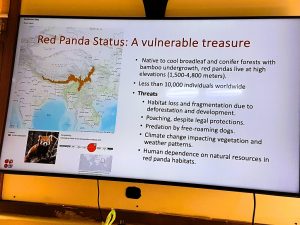

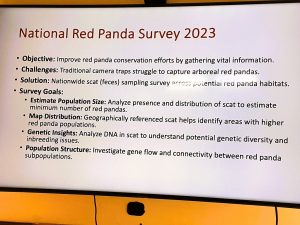

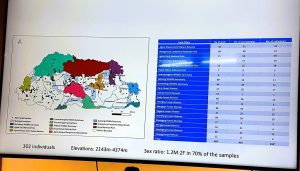

Then we continued our journey to the Wangdue Forest, where we were to trek the next day. In the evening, we took the opportunity to chat with Lungten, who has extensive knowledge of Bhutan's small felines (he wrote his thesis on the long-banded leopard). He told us that 302 pandas were present in the country, including 33 in the forest we were going to visit the next day. This figure comes from a study conducted between 2018 and 2023, on a specific area containing the preferred habitat of our small mammal.

Camera traps were set up there, and fecal samples were collected. The camera traps didn't yield much, but it was thanks to the samples collected that genetic studies were conducted to determine the different panda populations present in the country. The study revealed the presence of 302 individuals, but only in the studied area, which could indicate a slightly larger presence of the species.

Moreover, the study confirms the presence of both panda subspecies in Bhutan! According to Lungten, the main natural predator of the red panda here is the yellow-throated marten, but he confirmed that in places where the presence of "small cats" is proven (notably Temminck's cat and marbled cat), red pandas are not found. Bhutan is also a country where the tiger lives; they counted 131 at the last census. So there is no shortage of potential predators of the red panda here. But we will learn later that this is not its main threat.

Trek in mountains

On Sunday, November 17, 2024, at 8 a.m. sharp, we set off on the "Lungchu zay pilgrimage trail," a trek of about two hours (after a 1.5-hour drive on a mountain road), which takes us to the Buddhist temple "Lungchutse," at an altitude of 3,566 meters. Needless to say, we were literally breathless. At this altitude, the air is thinner, and each effort requires more energy.

So we stopped regularly, which allowed us to take the time to search the trees for the presence of our "prey", or any other animal species living in this region. We also took the opportunity to take photos of all the plants in the forest, to get a fairly comprehensive idea of the red panda's habitat. In the end, we saw a Darjeeling woodpecker, a Himalayan magpie, not very shy, which approached our meal place, a marten dropping, revealing the presence of the animal in these places, and a certain number of yaks, which we should not approach too closely... but no red panda!

Finally, the walk was pleasant, our guides very interesting, the temple magnificent, and the landscape sumptuous!

After having lunch at the top of the mountain, not far from the temple, we go back down to take the car and return to Thimphu for our interview the next day with the Royal Society for Protection of Nature (RSPN).

The Royal Society for Protection of Nature (RSPN)

RSPN was established in 1987 under the royal command of His Majesty the Fourth King of Bhutan as a civic NGO dedicated to the conservation of the Kingdom's environment. Its vision is to be a leader in conservation, ensuring that future generations of Bhutanese live in an environmentally sustainable society. Its mission is to inspire the people of Bhutan to take responsibility and actively engage in the conservation of the Kingdom's environment through education, community engagement, and the creation of sustainable livelihoods. Today, Her Majesty the Queen of Bhutan is the Royal Patron of RSPN.

The RSPN's work is structured around six conservation areas: (1) species and habitats, (2) wetlands and freshwater, (3) climate change adaptation and resilience, (4) waste and pollution, (5) sustainable livelihoods, (6) environmental education.

On Monday, November 18, 2024, we visited the NGO's headquarters for an interview with Dr. Kinley Tenzin, Executive Director; Tsheten Dorji, Head of the Sustainable Livelihoods Division; Tshering Dorji, Head of the Administrative and Financial Division; Jigme Tshering, Head of the Species Conservation Division; Dr. Lungten Norbu, a specialist; and a researcher. They began by introducing us to the association, its history, its missions, and its actions.

On Monday, November 18, 2024, we visited the NGO's headquarters for an interview with Dr. Kinley Tenzin, Executive Director; Tsheten Dorji, Head of the Sustainable Livelihoods Division; Tshering Dorji, Head of the Administrative and Financial Division; Jigme Tshering, Head of the Species Conservation Division; Dr. Lungten Norbu, a specialist; and a researcher. They began by introducing us to the association, its history, its missions, and its actions.

The RSPN works outside of protected areas, so as not to duplicate the government's efforts (DoFPS). Among other things, it has developed two conservation programs around two endangered species in the territory: the black-necked crane ("near threatened" on the IUCN Red List) and the imperial heron ("critically endangered" on the IUCN Red List). Other conservation programs like these are under consideration, but the NGO has not yet decided which species will be next, as many animals are endangered in Bhutan. The red panda is not one of the most at-risk species, but shares the same habitat as some of them. They can therefore benefit from the protection actions that will be implemented at the habitat level. The RSPN's main needs are financial and technical support, particularly in terms of knowledge and expertise (they already receive support for this from Japan and the USA).

Educational programs (for children and local communities) already exist, such as the "Nature Club" in certain schools, for three decades, with action plans such as replanting in the distribution areas of the two bird species for which the RSPN has conservation programs (the crane and the heron), the creation of "handbooks" on nature, the concept of climate change, etc.

UNESCO will initially help the NGO develop the "Nature Clubs" on a larger scale. We told them about the twinning booklet we created for Nepal, and they seemed interested. We'll send it to them so they can get a concrete idea of the content and decide if it might be worth adapting to Bhutan.

As for the research field, studies are possible, and they are already working with several Western countries, such as Germany, Austria, and the Czech Republic.

For them, the main threat to the red panda here would be the overexploitation of bamboo by the population, for many reasons. Perhaps a line of thought for a future replanting plan? The Forest Department, for its part, thinks that the red panda would be a good species for a conservation program, in terms of education, management, and also at the habitat level. Indeed, 60% of Bhutan's population lives in forests and the DoFPS already intervenes in the poorest communities, to help them find sustainable livelihoods. But we will learn more during our interview with the DoFPS members the next day.

Visit to the “Royal Takin Preserve”

The Bhutanese takin is the country's emblematic animal. In the early afternoon, we visited the Royal Takin Reserve, which is also a care center for deer, small mammals, and birds, managed by the Forest Department. This 3.4-hectare site includes large enclosures, some of which are interconnected, and several aviaries. The rescued animals are cared for there and then released, although some of them return to the reserve on their own. Walkways on stilts allow visitors to see the animals up close, and educational panels inform the public about the species they can observe (takin, muntjac, goral, resplendent lophophore, satyr tragopan, etc.).

On the other hand, Lungten explained to us that for small mammals, such as red pandas, it was more complicated because the site does not have a structure adapted for small carnivores. Since the CPPR is largely made up of animal keepers and works in collaboration with zoological parks, we could perhaps propose plans for a suitable building, or even set up a fundraising campaign if necessary?

After the tour of the reserve, we were received by the director of DoFPS, Mr. Karma Tenzin. He spoke to us about his expectations in terms of potential cooperation:

- In Bhutan, little research is being conducted on red pandas, in terms of biology, habitat, lifestyle... it would be interesting to propose such research to the MNHN, for example.

- For rescued red pandas, the Bhutanese have little knowledge of caring for them in captivity... What food ration should they be given, what protocol should be put in place for their release? We could also work on this topic, or even invite them to participate in the webinars we are going to set up with Sikkim and Darjeeling?

- Ecotourism: How can we build suitable structures to accommodate travelers and train guides? Samuel believes that Regional Natural Parks (PNR) will be able to answer this question more easily.

We took note of these complaints, to discuss them the next day, with other members of the DoFPS.

Meeting with the Nature Conservation Division of the Forestry Department

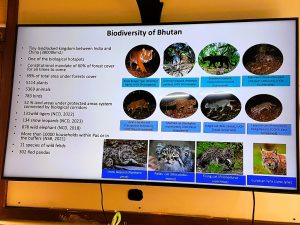

So, Tuesday, November 19, 2024, we are in the DoFPS offices, with Lungten, Norbu Yangdon, in charge of the protected areas section, and Choney Yangzom, in charge of human-wildlife conflict management. Norbu explains that "this is the first time that a French NGO has collaborated with this office. By the end, we should have a good understanding of the collaboration we can have." She begins with a presentation on nature conservation in the country.

52% of Bhutan's forests are managed by the government, either in the form of protected areas (network of protected areas, Ramsar sites and other effective area-based conservation measures, known as "OECMs"), sustainable forest management zones

52% of Bhutan's forests are managed by the government, either in the form of protected areas (network of protected areas, Ramsar sites and other effective area-based conservation measures, known as "OECMs"), sustainable forest management zones

(forest management units, community forests and local forest management areas) or others (transversal, management areas).

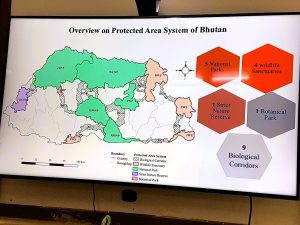

The protected areas network includes 5 national parks, 4 wildlife sanctuaries, 1 strict nature reserve, 1 botanical park, and 9 biological corridors. The protected areas are zoned into 4 zones: a core, preserved zone, where only research activities can be carried out, a transition zone (there may be traditional rights), a buffer zone, and a multi-use zone, for local activity. OECMs aim to provide protection beyond the protected areas. Key Biodiversity Areas (KBAs) aim to protect specific habitats (for orchids, imperial herons, red pandas, etc.). In total, there are 11 protected areas, 9 biological corridors, 11 KBAs, 9 high conservation value areas, 3 Ramsar sites, 21 forest management units, and 824 community forests.

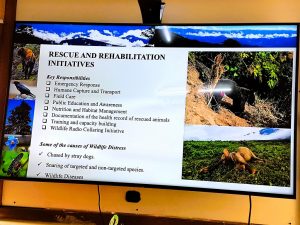

Norbu then discusses the approach to species conservation. According to the latest studies, Bhutan has 131 tigers, 134 snow leopards, 678 elephants, and 302 red pandas. The various activities are guided by species conservation action plans. There is a unit dedicated to rescue and rehabilitation.

They are responsible for emergency response, capture and transport, field care, public education and awareness, nutrition and habitat management, documentation of rescued animals' medical records, training and skills development, and wildlife radio collaring initiatives. They have protocols for the most common animals. Several animals have been collared (takins, tigers, dholes, elephants, snow leopards, and black bears). Their main issues and challenges are: land use change (rapid economic development), human-wildlife conflict, poaching for illegal wildlife trade/retaliation killing, pollution (solid waste, water, soil, and air pollution), invasive alien species (fauna, flora, stray dogs, etc.), and climate change and its impact on conservation.

Lungten continues with a presentation on red panda conservation in Bhutan. The department he works for (Species Conservation) coordinates, provides technical advice, develops technical regulations, guidelines, and protocols, develops conservation action plans, conducts surveys, monitors biodiversity, and coordinates with research institutes and universities in Bhutan and around the world. He collaborated with the Red Panda Network (RPN) in Nepal to draft the red panda conservation action plan.

Lungten continues with a presentation on red panda conservation in Bhutan. The department he works for (Species Conservation) coordinates, provides technical advice, develops technical regulations, guidelines, and protocols, develops conservation action plans, conducts surveys, monitors biodiversity, and coordinates with research institutes and universities in Bhutan and around the world. He collaborated with the Red Panda Network (RPN) in Nepal to draft the red panda conservation action plan.

Bhutan has recorded 5,114 plant species and 5,369 animal species (139 mammals). 10,000 households are part of protected area systems. Ecosystem services are worth USD 15.5 billion annually in Bhutan (nearly five times GDP), while forestry contributes 2.6% of GDP. Bhutan is renowned for its leadership in conservation and has received several awards for this.

Bhutan has recorded 5,114 plant species and 5,369 animal species (139 mammals). 10,000 households are part of protected area systems. Ecosystem services are worth USD 15.5 billion annually in Bhutan (nearly five times GDP), while forestry contributes 2.6% of GDP. Bhutan is renowned for its leadership in conservation and has received several awards for this.

Environmental conservation is one of the four pillars of Gross National Happiness. The fifth article of the constitution is entirely devoted to the environment. The Forest Department, established in 1952, is one of the oldest in the country. Recently, Bhutan has shifted its conservation measures towards a more community-based approach. The Forest Department collaborates with other sectors (Climate Change Department, national NGOs, etc.).

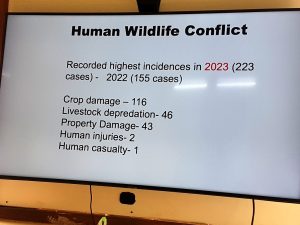

Conservation action plans target key species (tigers, red pandas, etc.). Bhutan has recently opened up more to ecotourism and conservation outside protected areas through sustainable practices. However, human-wildlife conflict is one of the biggest concerns. The first problem is crop damage, followed by livestock degradation. Furthermore, between 1995 and 2022, the tiger population increased from approximately 70 to 131, and tigers have been observed as high as 4,000 m.

But back to red panda conservation. A recent study (from 2018 to 2023) confirmed the presence of both subspecies (Ailurus fulgens fulgens and Ailurus fulgens styani) in the country. Moreover, for the Bhutanese, these are indeed two different species. But the study only considered potential locations where they thought they would find red pandas; further studies could refine this research. According to this study, the two main threats (but not the only ones) to red pandas are habitat loss and fragmentation. Interspecific competition can also potentially be a problem.

But back to red panda conservation. A recent study (from 2018 to 2023) confirmed the presence of both subspecies (Ailurus fulgens fulgens and Ailurus fulgens styani) in the country. Moreover, for the Bhutanese, these are indeed two different species. But the study only considered potential locations where they thought they would find red pandas; further studies could refine this research. According to this study, the two main threats (but not the only ones) to red pandas are habitat loss and fragmentation. Interspecific competition can also potentially be a problem.

But back to red panda conservation. A recent study (from 2018 to 2023) confirmed the presence of both subspecies (Ailurus fulgens fulgens and Ailurus fulgens styani) in the country. Moreover, for the Bhutanese, these are indeed two different species. But the study only considered potential locations where they thought they would find red pandas; further studies could refine this research. According to this study, the two main threats (but not the only ones) to red pandas are habitat loss and fragmentation. Interspecific competition can also potentially be a problem.

But back to red panda conservation. A recent study (from 2018 to 2023) confirmed the presence of both subspecies (Ailurus fulgens fulgens and Ailurus fulgens styani) in the country. Moreover, for the Bhutanese, these are indeed two different species. But the study only considered potential locations where they thought they would find red pandas; further studies could refine this research. According to this study, the two main threats (but not the only ones) to red pandas are habitat loss and fragmentation. Interspecific competition can also potentially be a problem.

Genetic diversity was compared with that of other countries, showing that there is transboundary and internal sharing of diversity within Bhutan. The Bhutanese red panda population shows signs of historical isolation and connection.

Genetic diversity was compared with that of other countries, showing that there is transboundary and internal sharing of diversity within Bhutan. The Bhutanese red panda population shows signs of historical isolation and connection.

Genetic data suggest a potential past decline followed by population growth (past bottleneck). This information is valuable for red panda conservation strategies in Bhutan. A larger study is needed as current data represent only a small fraction of the potential habitat. The study identified 302 red pandas in a limited area (6% of Bhutan).

This suggests a potentially large national population, given that suitable habitat covers 28.58% of the country. Further studies are crucial for accurate population estimation and targeted conservation.

- Genetic health : diversity is moderate, but signs of inbreeding (reduced genetic variation) exist, potential subpopulation with limited connections.

- Habitat fragmentation: It can hinder red panda movement and gene flow.

- Corridors and connectivity: Existing corridors in Bhutan are a starting point, research is needed to assess their effectiveness and location, strategic expansion can create a network for healthy red panda populations (corridors are currently designed for large carnivores but not specifically for red pandas).

Overall, collaborative efforts are needed to ensure the long-term survival of red pandas, and a well-designed corridor system can promote gene flow and population health.

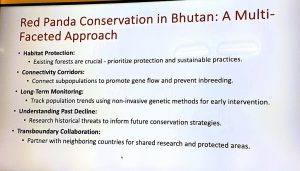

A multifaceted conservation approach:

- Habitat protection: Existing forests are crucial – prioritize protection and sustainable practices.

- Connectivity corridors : they connect subpopulations to promote gene flow and avoid inbreeding.

- Long-term monitoring: monitor population trends using non-invasive genetic methods for short-term intervention.

- Understanding past decline: research historical threats to develop future conservation strategies.

- Cross-border collaboration: partnership with neighboring countries for joint research and protected areas.

Upcoming work:

- Revision of the Red Panda Conservation Action Plan 2025-2034 funded by the

GEF-7 ecotourism project - Red panda habitat enrichment in Trashigang Forest Division,

funded by the World Wildlife Fund (WWF)

Collaboration envisaged with the CPPR:

- Education and awareness (can be done in the short term with the RSPN). Board game "the bamboo race": can be derived for other species, such as the tiger or the snow leopard. The CPPR would take care of the visuals itself with a graphic designer and then contact a company for printing.

- Research and interactions between species (The CPPR has access to a vast network of researchers and can easily communicate this to the forestry department, particularly with the MNHN)

- Rescue and rehabilitation (The CPPR can provide its expertise in zoo management, particularly for the construction of a building for small carnivores in the takin reserve, etc. The CPPR has specific protocols that can be shared.)

- Ecotourism (based on the red panda, in a red panda KBA = Range Area

Red panda breeding. Create an ecotourism site for the red panda, with awareness and education? (To be seen later, perhaps to be developed with the PNR) - Habitat conservation (also in a second step)

- General monitoring of biodiversity

We also discussed the webinar on best practices in maintaining captive red pandas with India, the forest government is very interested.

Finally, they were contacted by the RPN, and since we know them too, we

we could all work together.

At the end of the interview, we all ate together, along with other members of the Forestry Department and members of UNESCO, who had come for another meeting. We became friends and exchanged business cards. The UNESCO members offered us their help if it could be useful.

At the end of the interview, we all ate together, along with other members of the Forestry Department and members of UNESCO, who had come for another meeting. We became friends and exchanged business cards. The UNESCO members offered us their help if it could be useful.

En résumé, cette visite au Bhoutan s’est avérée très intéressante et enrichissante. Nous espérons qu’une belle collaboration pourra en découler !

Conclusion

So, this first India-Bhutan mission lived up to all its promises and even more! Our various interviews proved very promising, and we learned a number of things about red pandas. We look forward to continuing our discussions with our interlocutors to contribute even more to the preservation of our star animal!

Small downside on the return, be careful if you go to India, we were "kidnapped" by a taxi, who never wanted to take us to our hotel, but who took us to another, very shabby, and we were forced to pay for a room there because they were really insistent... and sadly, snow on our return to France made our bus cancel, and we almost didn't get a train home...

But these minor annoyances aside, if you pay attention to what you eat, what you drink, the water you use and if you don't spend too much time in big cities... your experience can be enriching and you might even be lucky enough to spot a wild red panda!

Acknowledgements

The CPPR would like to thank all the people without whom this mission would not have been possible and who made it possible, whether local or financial.

First of all, we would like to thank the Parc de Clères, which largely financed this 2024 mission.

Then, we obviously thank all the people we met in India and Bhutan:

- The Consulate (Mr Talpain, Samuel Bouchard and Anjita Roychaudhury)

- Minla Zangmu Lachungpa, veterinarian and biologist at Gangtok Zoo

- Mr Sangay Gyatso Bhutia, Director of Gangtok Zoo

- Dr Basavaraj S. Holeyachi, Director of Darjeeling Zoo

- Uttam Chandra Pradhan, who accompanied us to the Darjeeling Zoo and the breeding center

- Dr. Lungten Dorji, Species Conservation Officer at the Department

Forests and Parks - Norbu Yangdon, head of the Department's Protected Areas Section

Forests and Parks - The members of the Forest Department who accompanied us to India

as well as all the members of the RSPN who welcomed us, and all the members of the DoFPS that we met.