This article was written in 2016 by Jérôme Pouille, the creator of the website “pandas.fr”

The giant panda (Ailuropoda melanoleuca) was already known for millennia in the mysterious East when its existence was revealed to the Western world. For European scholars, the black and white bear remained a myth until March 1869, when Father Armand David, a French missionary and naturalist, discovered a copy in the south-western mountains of China.

Like its namesake, the red panda, the giant panda belongs to the order Carnivora, but over the course of evolution, it has shifted to a herbivorous diet, consisting almost exclusively of bamboo. Bamboo is readily available and readily available year-round, and this choice prevents the giant panda from competing for food. It consumes all parts of the plant, with seasonal preferences. In spring, for example, giant pandas are fond of newly sprouting bamboo shoots, which are highly nutritious. Depending on the opportunity, they may supplement their meal with berries, eggs, or even carrion.

The digestive system of the giant panda is not completely adapted to this diet, which is so particular for a carnivore. It only digests 17% of the bamboo it consumes and is therefore obliged to ingest large quantities, between 15 and 30 kilos per day depending on the season. Several characteristic adaptations have nevertheless been developed over the course of evolution: a digestive system lined with lubricating glands to facilitate the passage of bamboo, an adaptation of the skull to allow significant chewing force, large and flattened molars to grind bamboo. Finally, and this is undoubtedly the most characteristic adaptation, the giant panda has on its forelimbs, just like the red panda, a sort of thumb that is opposable to the other fingers: it is called the sixth finger of the panda and is in fact a bony outgrowth of the radial sesamoid bone. He uses it to grab the bamboo, peel it, shell it and bring it to his mouth.

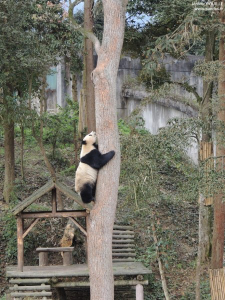

The giant panda usually weighs between 60 and 80 kg in nature; the larger ones can reach 110 kg. Females are usually smaller. In captivity, they weigh 80-130 kg. Their bodies measure 1.20-1.50 metres (head included). Its legs are covered with thick black hairs that ensure a stable gait especially on the snow. Its claws are sharp and they allow him to climb easily. It knows how to swim and it does not hibernate (bamboos are available all year round). In the wild, it rarely reaches the age of 20 years while in captivity, many exceed the 30 years.

Its bi-coloring could be a protective color in dense forest or snow but also allows individuals to recognize themselves. Its thick coat is covered with a layer of oil on its surface which facilitates its movements in the dense forest and limits the loss of body heat and the penetration of moisture.

Classified in turn with the red panda, then with raccoons, or even in a separate family, the classification of the giant panda has been the subject of numerous scientific controversies. Today, it is confirmed and accepted by the scientific community that the giant panda does indeed belong to the bear family (Ursidae).

The giant panda is a solitary animal. Males and females have their own territory and have little direct physical contact with each other outside of breeding periods or mother/young relationships. They have an anogenital gland that they use to mark their territory olfactorily and chemically, using variable postures that they adopt to mark more or less high. Marking, which takes place all year round, is more frequent during the mating season. The same is true for vocal communication, more developed and more audible from March to May. Scent marks and vocal signals allow the transmission of a great deal of information; they are highly individualized and act like calling cards capable, for example, of indicating the state of sexual receptivity of an individual or even the age and sex of the transmitter. For a solitary animal, this communication is crucial for the coordination and success of reproductive efforts. Especially since the female only accepts the male for 1 to 3 days per year, when she is at her peak of receptivity. Several males may compete for the same female, with the most experienced winning first. Each male can mate with several females, and the same female can accept other males after mating with her favorite.

After mating, individuals return to their solitary lives. Gestation time varies because the female undergoes embryonic diapause, a process during which the nucleus of the cell that will form the embryo floats for varying lengths of time in the uterus before implanting. Scientists believe this delay allows the cell to adapt to variations in food and altitude in the panda's range. The female will give birth to one or two cubs, very rarely three, in a den she has previously prepared in the hollow of a tree or a cave. The cubs are generally born in August or September, and the mother panda will raise only one; the others will die quickly, lacking sufficient energy to care for more than one cub at a time. A baby panda weighs only about 120 grams, or only 1/900th of its mother's weight, which is the largest difference in mammals between the weight of the mother and her baby. Its pink body is covered with a few short, sparse white hairs. Its eyes are closed and it is deaf. Its mother cares for it tirelessly, breastfeeding it several times a day and going without eating. The young grows rapidly and at the age of six months will resemble a miniature adult. By its first birthday, it weighs 20 to 30 kilos, feeds on bamboo, and will remain with its mother until it is 18 or even 30 months old, before establishing itself in its own territory. It will not mature until it is about 7 years old.

Only 1,864 giant pandas remain in the wild today, in six major mountain ranges in central China: the Qinling Mountains in Shaanxi and Gansu provinces, the Minshan Mountains in Gansu and Sichuan provinces, and the Qionglai, Daxiangling, Xiaoxiangling, and Liangshan Mountains in Sichuan province. Thirty-three virtually isolated populations spread across a territory of 2,576,595 hectares, generally between 2,000 and 3,800 meters above sea level, on the southeastern foothills of the Tibetan Plateau, in an ecosystem described as a "biodiversity hotspot" for its ecological richness and endangered nature.

The male's territory, which is 6 to 7 km² in size, may overlap with that of one or more other pandas, male or female. The female's territory is slightly smaller and includes a central area where the den is usually located. Pandas undertake seasonal migrations between their winter and summer habitats. They are active both day and night, with peaks of activity depending on the territory where they live. They spend more than 50% of their time eating.

Poaching, logging and massive deforestation, conversion of forests into agricultural land, expansion of cities, Unrestrained development of the Chinese population and associated development activities are the evils that have led in the past the last wild pandas to take refuge in a shrinking and fragmented habitat.

Habitat extirpation and fragmentation are the two threats that persist today and make it difficult for individuals to migrate, a natural process that is essential, especially in order to find a partner for reproduction and thus promote genetic exchanges, but also for young people who seek to establish their own territory after separation from their mother, or to search for alternative food sources in the case of bamboo death episodes, the almost exclusive food of the Chinese plantigrade.

Since the 1990s, China has made considerable efforts to protect its flagship species: creating a network of nature reserves (67 in total to date) which correspond to administratively protected portions of the habitat where human activities are controlled or even prohibited. They protect two-thirds of wild pandas but cover only slightly more than half of their habitat. In 1998, China introduced two programs that would give a boost of hope for the last wild pandas: the promulgation of a moratorium on deforestation and a program to convert farmland into forests.

At the same time, in situ conservation programmes will be initiated, with support for sustainable community development, with the premise that it is only by effectively meeting the needs of local populations and encouraging sustainable development practices that the long-term survival of pandas can be expected. These projects, led by the Chinese government in cooperation with the Chinese branch of WWF, aim to provide local people with the means to engage in sustainable alternative lifestyles while increasing their incomes and reducing the impact on panda habitat of environmentally damaging activities such as poaching, logging, collecting medicinal plants, cutting wood for heating and cooking, or unsuitable farming methods. These innovative conservation projects are accompanied by education and training of communities and local government officials on environmental issues and conservation practices.

Protecting the giant panda's habitat means protecting a unique, rich ecosystem that shelters hundreds of other animal and plant species under the panda's umbrella. More than 10% of the world's known mammal species live in China, and 18% of these are endemic to China. Currently, 179 mammal species share the same habitat as the giant panda, representing 32% of the mammals living in China. There are also 565 bird species, 31 reptile species, 92 amphibian species, and 132 fish species in the giant panda's habitat.

Who am I ?

Chengdu Giant Panda Ambassador ("Chengdu Pambassador" in English) is the title that brought me to China, the ancestral home of the black and white bear. Panda Ambassador means learning more about the species, understanding the threats it faces and its habitat, understanding how it is raised in captivity, and the research that mobilizes many Chinese and Western experts, but above all, sharing all this knowledge with as many people as possible, raising awareness, communicating, explaining, and educating about conservation.

I had the opportunity to share for three months the daily life of the keepers, veterinarians and scientists of the Chengdu research base on giant panda breeding (Chengdu research base of giant panda breeding), and then a world tour of zoos that display the giant panda in captivity where I was able to meet staff and conduct conservation education with the public.

I have always been an ambassador for the panda cause. The information and news website I created in 2002 (www.pandas.fr) is an illustration of this and helps raise awareness among schoolchildren, enthusiasts, the curious, and anyone who wants to unravel the mystery of the great bear cat, as the Chinese call it. I am also the author of the recent brochure "Giant Pandas, Ambassadors of Conservation" and the photo book "Giant Pandas Around the World."

To find out more:

Facebook : http://www.facebook.com/pandas.fr

Twitter : http://www.twitter.com/pandas_fr